A week after the Japanese occupation, a group of armed militia arrived at our house on 36 Boissezon and conducted a thorough search of the premises. What they found of interest was a stack of copper pipes stored in the flood cellar. These were to be replacements for some old piping. Six small, pungent bags hanging from the rafters also intrigued them. One fellow stabbed a bag with his bayonet, only to puncture and knock down one of Aunt Grace’s brandy soaked Christmas puddings, which needed to age until Christmas. They poked around some more, but turned up nothing but a couple of old bikes. Luckily, Wang, our chauffeur, had not yet dismantled our Rover sedan, or the parts would have probably been confiscated.

With some ceremony, the Imperial Seal was stuck onto door to the cellar, over the jamb. We were told not to remove it under any circumstances, or we would suffer serious consequences. All the servants were called to witness and then the group marched off.

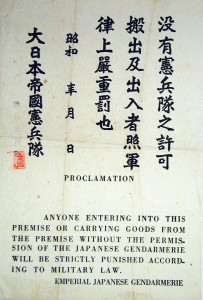

The seal itself looked like a sheet peeled of a book of cheap notes. The pattern was impressive, but the quality of the paper was flimsy. Countless thousands of these seals were posted all over the city, over doors, cabinets, closets, drawers, to prevent their owners from accessing their possessions. They were only removed when the occupiers decided to confiscate the contents. Our large second home on 131 rue Boissezon had been requisitioned and occupied by the Japanese military, so none of us at 36 were upset about a few copper pipes stored at 36. Life went on.

Some time later, as I was killing time in the garden, throwing a stick for my dog or trying to catch one of our chickens, I noticed a peeling scrap of paper on the cellar door. It had been rained on and was undecipherable, at least to me. So I scraped it off and wiped the door jamb clean. Before I knew it, I was surrounded by yelling servants, followed by my mother. “How could you be so stupid!” she shrieked, not for the first or last time.

I had removed the Imperial Seal! My father told me later that he could get no satisfaction from his pre-war chum, Mr. Ogawa, now Commandant. “Hans, that kid of yours has really done it. You are going to have her appear in court, and she has to explain herself. You have to hope they believe her!”

So a court day was arranged. I was to appear before a judge, to tell my story. I wore my best, a dress with a ruched bodice made by our English dressmaker. I had suffered plenty already from the pins thrust by Miss Rudge into my chest through the ruffled batiste. “Such a broad chest for a child her age!” she sniffed and, “Hold your stomach in!” She was actually trying to change my shape as she fitted my dress, without success. I was going on seven years old.

We arrived at the courthouse. It was a famous building, Marble Hall, a pretentious mansion on Bubbling Well Road, requisitioned from the Kadoorie family. It lived up to its name, as the floors, walls and various columns were all varieties of marble. The Kadoorie furnishings had been removed, and the place was fitted as a military courthouse and echoed with the sound of boots.

Dad held my hand tightly. “Don’t be nervous. Dad’s not going to let anything bad happen to you.” I must have looked miserable, so he added “Cheer up! I have a surprise for your afterwards.” My mother rolled her eyes and stayed home.

There were other felons waiting their turn, some with lawyers, who my father greeted with a handshake. I did not notice any other children, or anyone with a pretty, flowered dress like mine. One of the lawyers waved at me with a big smile. Dad repeated “Don’t be nervous. Just answer the questions. It’s going to be O.K.”

A stern Japanese military man escorted me to the judge. After he rummaged through some papers, the judge signaled to his interpreter, who boomed “Speak loud!”

I quavered “The seal was nearly all washed away from the rain. It didn’t look like anything important.” And “No I did not take anything out of the cellar.”

Suddenly the judge leaned over his podium. “How so young so high?” He actually smiled and spoke in English. I don’t know how I replied. He and the interpreter chatted for a few minutes, and then I was told to go home. It was over.

Our rickshaw was waiting for us outside. My father told him to take us directly to Kiessling and Bader, the celebrated German patisserie. I was still clutching his hand tightly as we sat at a table. “How about a chocolate éclair?” he asked. I nodded. “A cream puff?” “Yes, please.” They certainly didn’t stint on whipped cream. It was all over my face when I finished the second cake, and then threw up the whole lot over my ruched bodice right there in the restaurant.

photo of Imperial Seal from the collection of Greg Leck