The hotel where my mother and I spent the summer of 1939 faced the beach, a few hundred yards away. Early in the morning, I would go to the window, hiking myself onto my elbows. I would watch, fascinated, at a slow moving line from the water’s edge to the beach huts in front of the hotel. At a crawl, a couple of dozen of women wearing bags on their backs moved along the beach with mesh strainers in their hands. They were methodically scooping every bit of detritus left in the sand the day before. By breakfast they were done and the beach would be immaculate. I’d heard a guest complain “I lost my diamond earring on the beach, I’m sure. The hotel threatened the sweepers, but no one would admit anything!” I watched the line and wondered about the supposed lost jewel. If someone found it would she jump up with a scream? Or just pocket it without a word? I amused myself imagining this while waiting for my mother to emerge for breakfast. She was habitually a late sleeper.

We were summering in Tsingtao, at a well known resort. It was about an eight hour train ride from Shanghai, but we went the longer way by boat along the coast. A special feature of the resort that included our hotel was a fronton, built to accommodate teams of Jai Alai players that came up from Shanghai. They had a permanent location there but it was too hot for summer games. The fronton was a three walled court, open for spectator seating. The front wall was made of granite to withstand the balls slugged by the players out of baskets they held in one hand. The speed of the rock hard ball, smaller than a baseball, would be close to 150 mph. It is an exciting game, very fast, as one man hurls, the other guy catches the ball in his basket and catapults it back, and so it goes back and forth, with bets being taken moment by moment and players dashing, even climbing the side walls to capture the flying ball. This establishes the background for my jai alai story, which is not going to be an account of the game itself. After spinning my head back and forth watching the action a few times, I lost interest in it and was ready to meet my chum, Jo Jo at the beach.

The speed of the rock hard ball, smaller than a baseball, would be close to 150 mph. It is an exciting game, very fast, as one man hurls, the other guy catches the ball in his basket and catapults it back, and so it goes back and forth, with bets being taken moment by moment and players dashing, even climbing the side walls to capture the flying ball. This establishes the background for my jai alai story, which is not going to be an account of the game itself. After spinning my head back and forth watching the action a few times, I lost interest in it and was ready to meet my chum, Jo Jo at the beach.

Most of the long stay summer guests at the hotel were young housewives with little children. Their husbands worked in the sweltering City. Some dads, but not many, occasionally joined their families for a weekend. My father never did. My mother, our amah, and I settled into a pleasant suite for a couple of months. Because we traveled by sea, we were able to bring trunks full of clothing and accessories. My mother was an excellent long distance swimmer, and once on the beach, would disappear into the ocean for a very long time, leaving me on the beach with my bucket and spade. My learning to swim was out of the question. “You were afraid of the water,” my mother stated with finality. About my thwarted desire to ride a bike “You were afraid to fall off.” From my Dad, about my wish to learn to play the piano “You would spend too much time inside, practicing.” At the age of five, I had already embraced reading as an activity I could pursue without opposition.

In the evenings, the young mothers would make their way to the Jai Alai stadium, and try to sit right up front. The players were Basques; handsome and dangerous looking. They were dark, compact and virile. They played their game with explosive energy. Their black eyes snapped, their oiled and curly hair dripped sweat. They were the perfect complement to the cool appearing yet seething housewives.

My mother was small, chubby and bosomy. She sat upfront with a haughty air. She shaved her legs and underarms daily and carried face powder sheets with her wherever she went. “Look at them sweat,” she said disdainfully. I was sitting by her, when Echevarria, one of the players who was squatting in front of us between sets, turned and winked at me, with a big smile. He had hair springing from his armpits, hair on his chest and furry arms and legs. “Ugh!” said my mother, “look at all that hair.”

The little balls flew from the baskets attached to each man’s arm. The crowd screamed for their favorites. My mother powdered her nose and fanned herself. At that moment, Echevarria jumped up gracefully, and turned towards us. “Madam,” he began, and smiled a brilliant, wicked smile. To my surprise, my mother who kept herself out of the sun and was very pale, turned bright red. He leaned towards her and said something, and she held out her manicured hand. He took it between his sweaty paws, and I thought my mother would snatch it away. But all I could hear was a soft murmur as they leaned towards each other and started quietly talking.

That was when my mother officially met the famous Jai Alai player, Carlos Echevarria, and I got to ride the beach daily on his muscular shoulders.

After the game, we would join him in the hotel bar, where he drank anise wine and my mother daintily squeezed a lemon quarter into her gin and tonic. She and I would then have a low calorie meal, as she was watching her weight, while he dug into a hearty paella redolent of garlic and saffron. Although his English was rudimentary, they seemed to have a conversation going. I sidled off to join my friend, Jo Jo. Her French mother was gaily laughing with HER handsome player. Our amahs came out to find us, and we were escorted back to our rooms. I was still up, reading a book, when my mother returned to her adjacent room.

There was plenty of sun and paddling in the shallows with Jo Jo, who didn’t swim either.  Echevarria offered to teach us how to swim, without success. Boys flung themselves, yelling, into the waves, but most of the little girls wore pretty outfits and built sandcastles on the beach. They were not encouraged to play sports back then. Carlos (as we now felt free to him) was not really a swimmer himself. But he would haul me on his shoulders into knee deep water, or grab my wrists and swing me around, and tell me stories about the Basque fishing village he came from. When my mother returned to shore from one of her epic swims, he would take the beach towel that amah had ready and wrap it around my mother himself. He would tip amah and shoo her away. I rarely heard my mother laugh at home, but she was different here. She giggled, and laughed out loud a lot. She would sit and watch Carlos working out at the fronton, as all the players did for hours daily. Carlos had impressive muscle definition all over his body: he could lift me up with one arm. “Don’t hurt yourself,” my mother warned him, “she’s so heavy.” Carlos laughed a lot too; as easily as he lifted me and swung me around. “No she not heavy; she light, like bird!” Of course, that summer I developed a crush on Echevarria. But more, his big hearted, generous nature; the way he saw me as my parents never did, began to instill in me a new feeling of self esteem. He had to approach my mother through me, but he really liked me as a person, I felt, and would sit by me and move his finger over the page of a book I was reading, and try to mouth the English words. “You my teacher, pretty girl” he’d say, tousling my hair affectionately. Most of the players were married with children back home. They missed their families, so they were always ready to play ball or race along the beach or build a sandcastle with the summer kids.

Echevarria offered to teach us how to swim, without success. Boys flung themselves, yelling, into the waves, but most of the little girls wore pretty outfits and built sandcastles on the beach. They were not encouraged to play sports back then. Carlos (as we now felt free to him) was not really a swimmer himself. But he would haul me on his shoulders into knee deep water, or grab my wrists and swing me around, and tell me stories about the Basque fishing village he came from. When my mother returned to shore from one of her epic swims, he would take the beach towel that amah had ready and wrap it around my mother himself. He would tip amah and shoo her away. I rarely heard my mother laugh at home, but she was different here. She giggled, and laughed out loud a lot. She would sit and watch Carlos working out at the fronton, as all the players did for hours daily. Carlos had impressive muscle definition all over his body: he could lift me up with one arm. “Don’t hurt yourself,” my mother warned him, “she’s so heavy.” Carlos laughed a lot too; as easily as he lifted me and swung me around. “No she not heavy; she light, like bird!” Of course, that summer I developed a crush on Echevarria. But more, his big hearted, generous nature; the way he saw me as my parents never did, began to instill in me a new feeling of self esteem. He had to approach my mother through me, but he really liked me as a person, I felt, and would sit by me and move his finger over the page of a book I was reading, and try to mouth the English words. “You my teacher, pretty girl” he’d say, tousling my hair affectionately. Most of the players were married with children back home. They missed their families, so they were always ready to play ball or race along the beach or build a sandcastle with the summer kids.

By the end of the summer, there had been a scandal, not surprising. One housewife lost it completely for Arriaga, one of the principal players. She sold her jewelry, and tried to bribe her amah to take her three year old daughter home. She planned to travel with her lover back to Shanghai. It was an impossible scheme, of course. The husband appeared; the hunky lover turned out not to be at all keen to elope. Basque players were and still are mostly very religious Catholics; not ready for more than a brief fling. There was plenty of gossip and taking of sides among the summer ladies, but in the end, everyone went home, discarding this season’s dresses, sandals, sun hats and lovers. “Will we see Carlos in Shanghai?” I asked my mother. “Of course not!” my mother snapped,” Why would we?” And that was the end of that story, except for an exchange of pebbles between me and Carlos on our last day.

The main fronton in Shanghai was located on the Rue des Soeurs, the same street as my school. But the entrances must have faced different directions as I never ever saw a Jai Alai player in that neighborhood. The whole, hot, charged summer faded away like a dream.

photos

The Jai Alai basket, or cistera

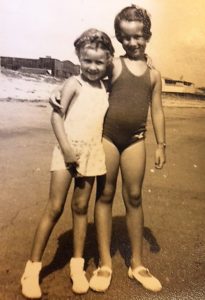

Jo Jo and Joan in 1939