Jack and I, and our 5 year old son, John, were tagged and housed together in a cubicle room at Yu Yuen camp. We shared our hut with the Currie family. The Japanese found  out that John Currie was an amateur radio enthusiast and ordered him to repair their radio sets; all of ours had been confiscated, of course. While John was repairing their equipment, he gradually stole enough parts to build a short wave receiver. A Chinese mem

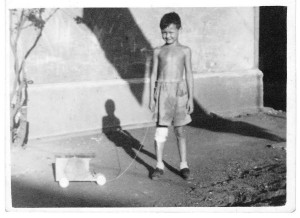

out that John Currie was an amateur radio enthusiast and ordered him to repair their radio sets; all of ours had been confiscated, of course. While John was repairing their equipment, he gradually stole enough parts to build a short wave receiver. A Chinese mem ber of the Shanghai constabulary smuggled in the valve for the set, and a wire curtain rod was used as an aerial. The wheels were milk can tops. John was able to build the radio set into a small framework, which when closed would appear to be a child’s toy truck. My son and the Currie daughter played with the truck on the porch of our hut, right in front of the Japanese guards. In the evening, we posted the kids outside the hut to watch for approaching guards. Meanwhile, I kept the set inside and took down, in shorthand, the 6 pm news from General MacArthur’s headquarters in Australia. I’d transcribe them into longhand and circulate the bulletins among the internees. The Japanese were suspicious, of course, and constantly searched, inspected and counted everyone. They would turn all lights off for days, leaving us in total darkness. Was I afraid for myself and my family? Sure, I was petrified as I watched my boy walking around with his truck. But

ber of the Shanghai constabulary smuggled in the valve for the set, and a wire curtain rod was used as an aerial. The wheels were milk can tops. John was able to build the radio set into a small framework, which when closed would appear to be a child’s toy truck. My son and the Currie daughter played with the truck on the porch of our hut, right in front of the Japanese guards. In the evening, we posted the kids outside the hut to watch for approaching guards. Meanwhile, I kept the set inside and took down, in shorthand, the 6 pm news from General MacArthur’s headquarters in Australia. I’d transcribe them into longhand and circulate the bulletins among the internees. The Japanese were suspicious, of course, and constantly searched, inspected and counted everyone. They would turn all lights off for days, leaving us in total darkness. Was I afraid for myself and my family? Sure, I was petrified as I watched my boy walking around with his truck. But we did what we did to survive with dignity. We organized schools, sick bays, sanitation and entertainment. We even had a piano until one night a Japanese guard interrupted our concert by unsheathing his sword and slicing through the piano chords. But we kept on with our music; someone had a harmonica!

we did what we did to survive with dignity. We organized schools, sick bays, sanitation and entertainment. We even had a piano until one night a Japanese guard interrupted our concert by unsheathing his sword and slicing through the piano chords. But we kept on with our music; someone had a harmonica!

We were obsessed with food, or rather, the lack of it. The Red Cross sent us packages, but we rarely got them. When there was a measles epidemic at the camp, the Japanese commandant issued each child one egg. Some weevilly rice appeared now and then, and we knew we had to consume the bugs for protein. Any valuables we had, we traded with Chinese outside the camp, which was only sealed against our escape. Items could be passed back and forth, including parcels from friends and relatives on the outside. My sister, Di, could always be counted on for unusual concoctions; she had the best of intentions. We soaked and ground up soybeans and corn used for animal feed; we could buy sacks of these cheaply. The soybeans we turned into milk, high in protein, and the corn into a mush, not worth recollecting .

The human body can stand an awful lot, we learned that. I don’t think anything else that could happen to me now would bother me because we hit rock bottom then. When you are cold, hungry, and in the dark, not much else could happen to frighten you.

We heard later that my brother, Ed, only twenty when he went into a different camp, in Pootung, had kitchen detail and was put in charge of keeping the fire going for cooking. Ed was always ready for fun and high jinks, and secretly paid the coal guy to smuggle a bottle of cognac in the coal. Probably not that often! We also heard, sadly, that the Japanese closed down the popular Canidrome, and slaughtered the greyhounds for food. Ed managed to get some of that meat for his group. Tough and stringy as it was, he claimed it tasted a lot better than the rats he used to trap. Crisp fried cockroaches were a tasty snack, rich in protein.

We all suffered from malnutrition when we got out of camp. The American forces showered us with K rations, which included milk powder, canned butter, processed cheese, Spam and Hershey bars, and best of all, cigarettes, which we hadn’t seen in years. We gorged ourselves at first and got quite sick until we learned to pace ourselves.

The American forces showered us with K rations, which included milk powder, canned butter, processed cheese, Spam and Hershey bars, and best of all, cigarettes, which we hadn’t seen in years. We gorged ourselves at first and got quite sick until we learned to pace ourselves.

Our prewar servants, Hern Ling, our son’s baby nurse, and her husband Bing Sung, previously our handyman, who later became a construction foreman, met us at the gate of the internment camp as soon as it opened. They immediately took care of us. They cleaned our filthy, emptied out apartment, washed our clothes, cooked our food, did our shopping, etc. We were a pathetic, sickly family at first.

They were at the wharf to see us off when we left Shanghai soon after for Sydney, Australia on the AMS Reaper. This began our circuitous journey through three continents. We were all in tears. We had no money to give Hern Ling and Bing Sung, as we only had twenty five dollars to our name. We never saw them again.

photos by AP of the radio, taken after the war

photo of John with the radio

a sample K ration