The Diaspora Part 2

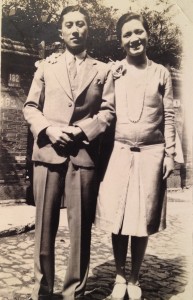

The only casualty was Ruby, the most beautiful and glamorous of the Harvey sisters. Ruby had had many lovers, a full length leopard fur coat and a wardrobe of party dresses. I remember her looking fabulous in that boxy coat at a time when fur was in style. She dressed beautifully, and always had a handsome boyfriend. But eventually she and an American army lieutenant fell in love. The war forced them to part in 1941,

and a wardrobe of party dresses. I remember her looking fabulous in that boxy coat at a time when fur was in style. She dressed beautifully, and always had a handsome boyfriend. But eventually she and an American army lieutenant fell in love. The war forced them to part in 1941, and she was at the dock in her leopard coat to kiss him goodbye as he went off to battle. He returned, as promised, as soon as the War ended. They had a passionate reunion, but he then confessed that he could not marry a Eurasian girl, or he would be expelled from the army. In fact, he admitted that he had become engaged to a girl in the US. Soon after, Ruby contracted spinal meningitis and died in the hospital a few weeks later. She was twenty nine. “She turned her face to the wall,” My mother said, in tears, “she did not want to live as a cripple. She did not want to live without the man she loved.”

and she was at the dock in her leopard coat to kiss him goodbye as he went off to battle. He returned, as promised, as soon as the War ended. They had a passionate reunion, but he then confessed that he could not marry a Eurasian girl, or he would be expelled from the army. In fact, he admitted that he had become engaged to a girl in the US. Soon after, Ruby contracted spinal meningitis and died in the hospital a few weeks later. She was twenty nine. “She turned her face to the wall,” My mother said, in tears, “she did not want to live as a cripple. She did not want to live without the man she loved.”  Her lover returned to the US with an armload of photos and memories; of himself and Ruby at parties, at the beach, horseback riding, hiking, traveling to Tsingtao, always hugging and kissing each other, always inseparable. The U.S. military had zero tolerance for mixed marriages. Many intelligent, well educated and beautiful Eurasian girls were abandoned by their gallant boyfriends in uniform.

Her lover returned to the US with an armload of photos and memories; of himself and Ruby at parties, at the beach, horseback riding, hiking, traveling to Tsingtao, always hugging and kissing each other, always inseparable. The U.S. military had zero tolerance for mixed marriages. Many intelligent, well educated and beautiful Eurasian girls were abandoned by their gallant boyfriends in uniform.

Phyl and her English husband took off for Australia, but all Jack found there was menial work and lodging in a hostel. “We didn’t feel welcome; there was no place for us to grow.” They then shifted to England and also had a hard time, in a country that was taking many years to recover economically from the war. Jack decided to try Canada, and sent for his family, which by then included another son, as soon as he found work in Guelph. They finally ended their circuitous journey there, and the farm they acquired is still in the family today. Jack was a strong, hardworking, hard drinking English country boy from Lancashire. He had been a head jail warden in Shanghai, and had executed a few criminals with one shot to the head “we had to save on ammunition.” In Canada, in addition to his job, he hunted moose and volunteered to train teenagers in survival skills. I remember visiting the farm, and being taken to the basement, to view in the gigantic freezer, Jack’s meat storage. “I got six hundred pounds of meat from that one moose,” he proclaimed. He shot deer in season, aged, prepped and stored the meat. One son, John, also had a farm, where he and his wife bred chickens, and had a yearly gathering of friends and family who formed an assembly line to slaughter, de-feather and cut up a couple of dozen birds. Everyone went home with the best tasting chicken imaginable. John had retired as a senior pilot for Air Canada, and was able to indulge his fantasy of being a farmer. Phyl, Jack’s wife and John’s mother, who we may recall having a manicure while snoozing in bed back in Shanghai days, had her part in this bucolic scenario. She became a champion maker of pot stickers. If there ever had been a contest, she would have won it hands down. She would start with huge amounts of dough, pork, shrimps, mushrooms and so forth, and rapidly turn them into rows and rows of dumplings, a shot of whisky by her side. There was a system where these were stacked and also stored in the giant freezer. Jack installed a generator down there to avert a possible power outage.

They then shifted to England and also had a hard time, in a country that was taking many years to recover economically from the war. Jack decided to try Canada, and sent for his family, which by then included another son, as soon as he found work in Guelph. They finally ended their circuitous journey there, and the farm they acquired is still in the family today. Jack was a strong, hardworking, hard drinking English country boy from Lancashire. He had been a head jail warden in Shanghai, and had executed a few criminals with one shot to the head “we had to save on ammunition.” In Canada, in addition to his job, he hunted moose and volunteered to train teenagers in survival skills. I remember visiting the farm, and being taken to the basement, to view in the gigantic freezer, Jack’s meat storage. “I got six hundred pounds of meat from that one moose,” he proclaimed. He shot deer in season, aged, prepped and stored the meat. One son, John, also had a farm, where he and his wife bred chickens, and had a yearly gathering of friends and family who formed an assembly line to slaughter, de-feather and cut up a couple of dozen birds. Everyone went home with the best tasting chicken imaginable. John had retired as a senior pilot for Air Canada, and was able to indulge his fantasy of being a farmer. Phyl, Jack’s wife and John’s mother, who we may recall having a manicure while snoozing in bed back in Shanghai days, had her part in this bucolic scenario. She became a champion maker of pot stickers. If there ever had been a contest, she would have won it hands down. She would start with huge amounts of dough, pork, shrimps, mushrooms and so forth, and rapidly turn them into rows and rows of dumplings, a shot of whisky by her side. There was a system where these were stacked and also stored in the giant freezer. Jack installed a generator down there to avert a possible power outage.

One of the brothers, Sam, had a good job with a British firm, and settled in Hongkong with his wife in a smart flat in the Peak neighborhood provided by his English employers. After he retired, his company tried to wrestle his apartment away from him, but Sam, always the smartest boy in his class, managed to hang on till the end. “But we couldn’t help being robbed by the locals,” he laughed, “the bars over our windows didn’t stop them.” There was no air conditioning, so windows were kept open in hot weather. Felons would creep up to an open window armed with a long pole ending in a hook. They managed amazing feats, extracting valuables deep in rooms, through the narrowest bars, with their rudimentary tools. “They could open drawers with their hooks, and empty out the contents. We could never figure out how!”

My father ended up in Hongkong, as well, and acquired a new family, consisting of a well off Chinese widow and her teenaged children. He never revealed this to me or my mother, who kept waiting for him to join her after she left Hongkong for England and later for the US. One day, after I was notified that my Dad had died, I got a long letter from a girl with a Chinese name. She outlined a story where my father had befriended her widowed mother and her two brothers and herself. He lived with them and had become their beloved second father. He saw them all through school and university. She wrote “he always spoke about you as the most wonderful girl in the world. You were the person he loved most of all. He kept your photo on his bureau. I would look at it and think how beautiful you are, Joan!” This was the first I ever heard of Dad’s second family. In letters, he had implied that he lived alone in a small flat…that was why whenever I threatened to visit him in Hongkong, he explained regretfully that he couldn’t host me. This letter knocked me flat. I couldn’t even bring myself to reply. I was angry at first, but over the years I have come to terms with this man, who really did love me in his own way, from a distance. I’m glad he spent his later life with an appreciative family. The only thing he and my mother ended up having in common was arthritis, quite severe in her case. At the age of seventy, I suddenly developed very painful, creaky knees, and realized this was their gift to me.

This letter knocked me flat. I couldn’t even bring myself to reply. I was angry at first, but over the years I have come to terms with this man, who really did love me in his own way, from a distance. I’m glad he spent his later life with an appreciative family. The only thing he and my mother ended up having in common was arthritis, quite severe in her case. At the age of seventy, I suddenly developed very painful, creaky knees, and realized this was their gift to me.

The youngest brother, Ed, met an American nurse in Shanghai. He and Ellen married, went to California, had four children, and spent the rest of their lives in a sprawling house in a typical American suburb there.

I peregrinated from China to the US, acquiring US citizenship through marriage, then lived in California, New York, Honolulu, Paris and Bristol, England before definitively settling in New York City. I finally feel I am in right place for a wandering soul to settle down.

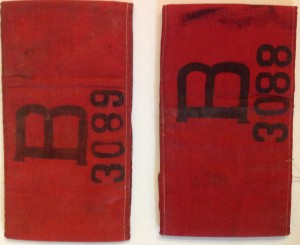

Ruby in her coat; on the dock in 1941; with her boyfriend

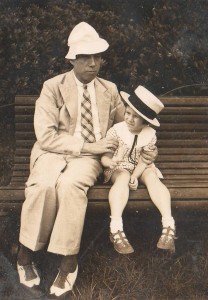

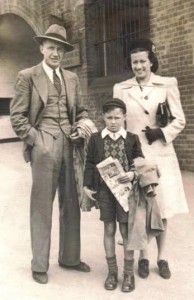

Jack, Phyl and John in Australia

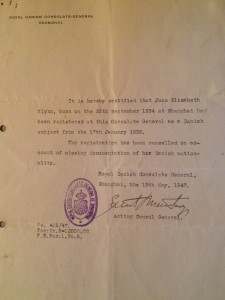

Dad in his 70’s with Jack Shute, in Hongkong